When a bulldozer rumbles through a shanty town or a low-income estate in Nairobi, the sound reverberates far beyond crumbling iron sheets and swirling dust. It carries a complicated promise: renewal, dignity, a city reimagined. But for many residents, that promise feels more like displacement, risk, and uncertainty.

In recent years, the Kenyan government has intensified a campaign of demolitions in Nairobi, particularly around riparian (river-bank) areas, under the banner of affordable housing development. Authorities and political leaders argue this is a bold leap toward transforming high-risk, polluted land into safe, modern housing for vulnerable populations. Critics, however, warn that many of the people being removed risk never benefiting from what is built in their place.

The Policy Logic: River Revitalization Meets Housing

At the heart of this demolition drive is the Nairobi River Regeneration Project, a multi-billion-shilling intervention that combines environmental cleanup, infrastructure upgrades, and affordable housing. The government describes it as a “once-in-a-generation” chance to reclaim polluted river corridors, reduce flood risk, and deliver social housing for displaced residents.

In 2025, Nairobi City County gazetted a Special Planning Area (SPA) for the river corridor, stretching roughly 60 meters on either side of the river. This SPA is designed to guide orderly redevelopment: wetlands, public parks, sewer lines, markets, and housing. The stated aim: “urban renewal with dignity,” not mass eviction.

According to Mumo Musuva, vice-chair of the Nairobi Rivers Commission, residents in the 30-meter riparian buffer will be supported to move into newly-built affordable homes nearby, and they will have priority in owning them. The project is not purely environmental; it’s being framed as social justice, with an environmental angle.

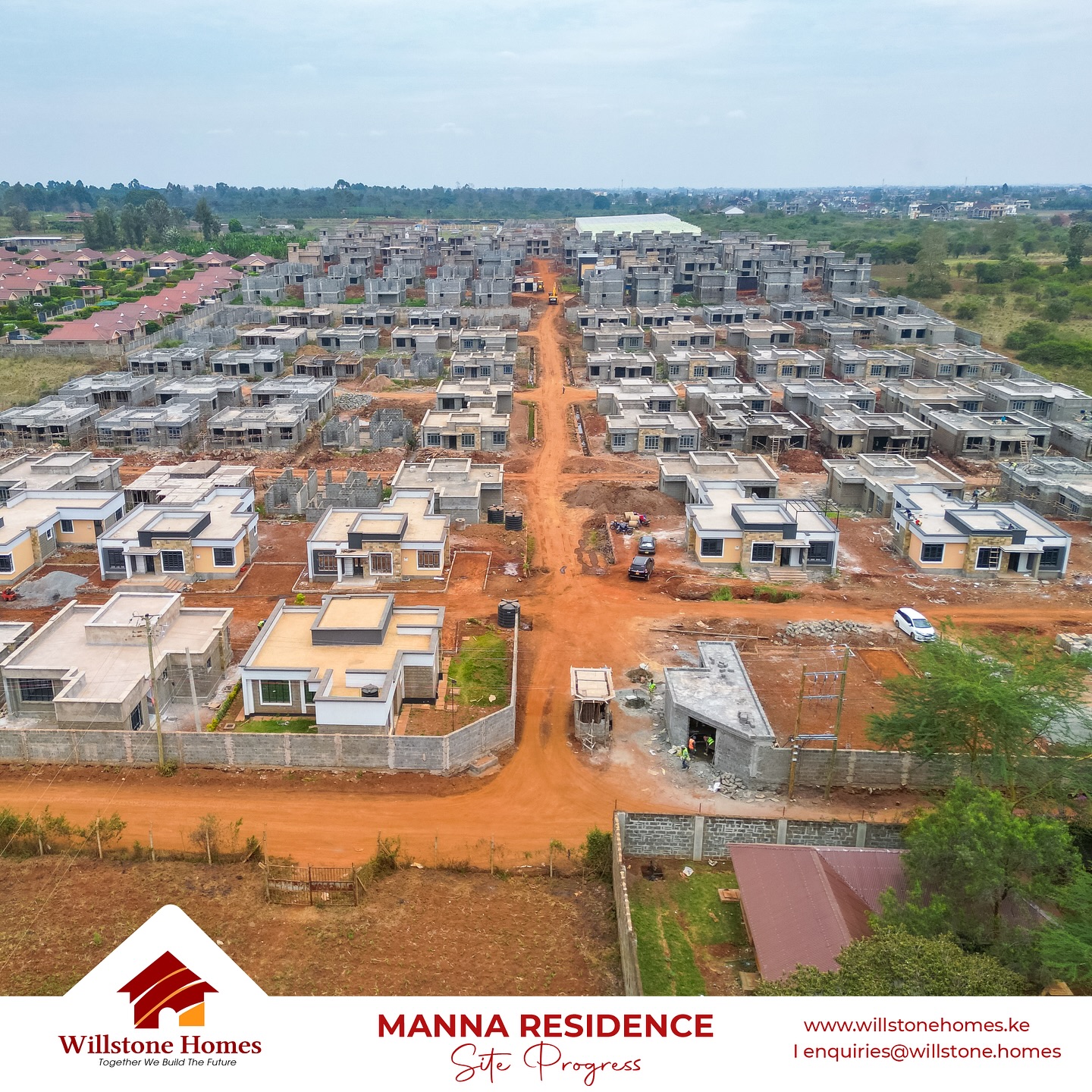

President William Ruto has repeatedly linked the demolition-resettlement drive to his Affordable Housing Programme. He has pledged 40,000 housing units to accommodate people displaced from riparian reserves. Moreover, he says the houses will be built quickly, and the project will also generate employment for thousands of youth under a so-called “Climate Work” programme.

Government officials say the plan is not to displace people indefinitely, but to reincorporate them into a “regulated, upgraded, more equitable” urban fabric. As Lands CS Alice Wahome explained before the Senate, the vision includes social housing units, modern markets, infrastructure—and employment.

The Human Cost: Lives on the Line

Yet on the ground, many residents see the bulldozers in a different light: as a threat to their homes and their livelihoods.

In Kayole, for example, the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) has called out “unlawful and arbitrary demolitions.” According to KHRC, some of these demolitions were carried out despite court orders barring eviction until due legal processes are followed. Families have been left homeless, and the involvement of state actors has raised serious concerns about complicity.

In Makongeni, Jericho, Bahati, Shauri Moyo, and other long-established estates, the picture is equally fraught. Embakasi East MP Babu Owino claims that demolition plans target generational homes — permanent structures where families have lived for decades — and that the compensation being offered is woefully inadequate. He has warned that the “token” payouts do not reflect the true cost of these homes or the disruption to people’s lives.

According to Owino, affected households are being offered only KSh 150,000 per house — a sum he argues is nowhere near enough to replace a home, especially for families of 3–5 people. He has also challenged the government on the affordability of the replacement housing: units in some of the “affordable” housing projects, particularly in areas like Mukuru, reportedly cost KSh 2 million or more, putting them out of reach for the low-income earners being displaced.

Rights, Contracts, and Double Standards

The debate quickly turns to legal and moral foundations. Senators have questioned the uneven application of demolition enforcement, accusing the government of targeting vulnerable, low-income communities while sparing wealthier or more formal structures upstream.

Lands CS Alice Wahome has responded by saying that the government is focusing on “pollution hotspots” rather than indiscriminate removal. But she also stated that many of the residents being affected don’t legally own the land under their feet — a point she uses to justify limited compensation. This stance has ignited fierce debate over property rights, historical injustice, and the meaning of “affordable housing” in a context where tenure is complicated or informal.

Adding to the tension, Nairobi Governor Johnson Sakaja has tried to calm fears. He has publicly vowed that any relocation will be handled fairly, and that displaced residents will be given priority in new social housing projects. But to many, such assurances ring hollow without strong legal guarantees, clear allocation plans, and a binding resettlement schedule.

Displacement Without Return?

One of the biggest criticisms centers on whether the very people whose homes are being demolished will ever actually benefit from the housing being built. Academic research suggests that past government commitments on affordable housing have often failed to reach the lowest-income residents living in informal settlements. There is a risk that the new housing stock will be too expensive, or allocated in ways that exclude those most in need.

Community advocates warn of a de facto gentrification: replacing informal, low-cost structures with “affordable” units that remain economically out of reach for many displaced residents. Indeed, MP Owino has explicitly questioned how low-wage earners will afford homes priced in the millions. Without clear financial mechanisms—rent-to-own, subsidies, long-term financing—many may be left out.

Another flashpoint is compensation. The government’s claim that some evictees do not legally own their land complicates the picture, but it also raises important ethical questions: if people have lived in a home for decades, does a small “token” payment truly make amends? And if new homes are not fully guaranteed for them before demolition happens, relocation could mean permanent exclusion rather than a dignified reset.

A Risky Social Engineering Experiment

Viewed from policy and planning angles, the river corridor regeneration is ambitious and potentially transformative. The idea of reclaiming degraded land, adding infrastructure, integrating green spaces, and building dense but dignified housing is compelling. It could improve health, reduce flooding, and optimize land use in the city.

The employment component is also real: tens of thousands of youth are reportedly being hired to help with the cleanup via the “Climate Work” programme. And for those who gain access to the social housing units, there may be long-term economic benefits: safer housing, better infrastructure, titles, and possibly upward mobility.

Yet the ethical and practical risks are non-trivial. Displacing marginalized communities without robust safeguards, meaningful participation, or enforceable rights can exacerbate inequality and perpetuate cycles of vulnerability. Without transparent mechanisms for allocating the new homes, the project could deepen social stratification rather than reduce it.

There is also a profound licensing risk: could this set a precedent for future demolitions under the guise of “affordable housing”? If the poorest are continuously moved around and never truly integrated into the benefits, the model becomes a tool of exclusion rather than inclusion.

What Needs to Be Done

For the project to deliver on its promise — and not just its rhetorical sheen — several critical steps must be taken:

- Transparent Resettlement Framework

- A public, binding resettlement plan should be published, detailing exactly how many units will go to displaced persons, when, and under what terms.

- There must be priority allocation for current residents, especially those who have lived along the river for years, and mechanisms to ensure they receive titles or long-term leases.

- Robust Compensation

- Compensation should account not just for the physical structure, but also for lost social networks, livelihoods, and non-monetary costs.

- An independent body (e.g., civil society + legal experts) should audit compensation offers and negotiate fairer terms when needed.

- Affordable Financing Models

- The “affordable” homes must be realistically affordable. The government should explore rent-to-own schemes, heavily subsidized mortgage options, or cross-subsidy models.

- Tailored payment plans are needed for low-income families whose monthly earnings will make traditional mortgages untenable.

- Community Participation and Accountability

- Affected community members must be meaningfully involved in the planning, design, and ongoing management of the housing developments.

- Social impact assessments should be mandatory and publicly disclosed.

- An independent oversight committee (including civil society, county government, and relocated residents) should monitor implementation.

- Tenure Security

- Ensure that the relocated residents receive legal security of tenure — either in the form of title deeds, long-term leases, or legally enforceable rights.

- Avoid models that push out previous residents in favor of speculative investors or wealthier buyers.

- Phased Demolition Linked to Delivery

- Demolitions should be closely tied to the availability of replacement housing. In other words: build first, then demolish.

- Temporary accommodation should be arranged for affected families where necessary, and no one should be left homeless simply because their structure was removed.

- Monitoring and Legal Redress

- Civil society, human rights organisations, and legal actors must have a formal role in oversight.

- Court mechanisms should be available and accessible for those who believe they have been wrongly evicted or inadequately compensated.

The Stakes Are High

This is not just a housing policy. It’s a socio-political experiment. If done right, it could signal a new era in Nairobi’s urban development: one where environmental regeneration, social housing, and economic inclusion go hand in hand. The river’s polluted banks could become a green, walkable corridor; vulnerable communities could be uplifted into formal housing; and a historical liability — squatter settlements on ecologically fragile land — could be transformed into a sustainable asset.

But if done poorly, the project risks reinforcing the very injustices it claims to correct. Poorer residents could be pushed to the peripheries. Those with linkage or political backing might capture the benefits, while marginalized communities are left out. Without careful design, accountability and genuine inclusion, this could be gentrification under the guise of social justice.

A Vision That Demands Vigilance

Nairobi’s demolition-for-housing campaign is, by any measure, bold. It is a high-risk, high-reward gambit: environment meets development, public good meets private rights, restoration meets displacement.

The narrative the government sells is powerful: reclaiming riverbanks, restoring dignity, building homes. But to turn that narrative into a reality that benefits everyone, especially those most vulnerable, requires more than bulldozers. It demands transparency, fairness, a legally enforceable resettlement plan—and most of all, trust.

As the city hurtles toward 2027, when many of these projects are slated to take shape, Nairobi’s future could be defined not just by high-rise apartments or pretty riversides, but by how well its poorest residents are woven back into the fabric of a renewed city — not just as observers or bystanders, but as rightful, secure citizens.